Hi everyone. Long time no see.

If I remember right, last time you heard from me was in mid-January. A solid three months ago. Around then, I was still trying to figure out what we were going to be doing, bleeding a bit of optimism and waxing philosophic about the meaning of life or something. Sounds about right.

But around then or just after, the bottom really fell out in more ways than one. From then on, I tried to sit down and write more than a few times, but nothing would emerge. Well, nothing I was proud of. I didn’t understand what happened then, nor did I really for the entire rest of the trip – but I genuinely couldn’t bring myself to put e-words down on e-paper. Entering my third week back in the States, I’ve been processing continuously, and finally feeling a little clarity. So if you’re interested, I feel like I owe it to the people who faithfully followed – and myself really – to revisit a little bit. Anyway.

So, I mentioned earlier that the bottom fell out. I’m referring primarily to my ability to write, but also to the general state of things as they stood in Liberia. I’ll revisit briefly starting at the very beginning, to provide a little context. In November, before I left, there was a big push from the powers that be, to get to Liberia very quickly and get an ETU up-and-running. I didn’t know this at the time, but the number of Ebola cases had been trending downward since August, at least where I was going to be. Very simply, the U.S. government was really slow in getting the humanitarian ball rolling, and there were two big consequences. First, they threw a huge amount of money at the problem (in my opinion, to take the heat off for being way behind) with poorly-defined and incomplete regulations and oversight. Second, the overall attitude was super-rushed. One time last year, I had an appointment I was late for at the DMV. I was streaking out the door, but needed certain documents in a certain order I had not, of course, laid out in advance. So I just grabbed every white paper within arm’s reach, threw them crumpled and mangled in my bag, backed out of the driveway and proceeded to forget my photo-ID. For some reason, the DMV lady wouldn’t accept my six-year old cousin’s crayon portrait of Severus Snape in its stead, so the trip was a wash. Swap Liberia for the DMV and a mess of papers for six-billion dollars, and you get a little idea. It was just a bad tone for things.

I’m sure you can imagine how well things go when a government holding a six-billion dollar suitcase for combatting a deadly, pandemic virus is rushing anywhere. At my ground level vantage, this was demonstrated by the embarrassingly goofy design of the initial ETU (“OK, there’s no door here, so how do I walk into that room?” and “Do you think we should put the electrical box outside the hot zone so we don’t have to ask the Ebola victims to trip breakers for us between pukes?”) and just an overall pressure to hurry-up. Hurry to get training done (“maybe just skip a few unimportant aspects?”) hurry to finish construction and hurry to open our ETU up. We were actually told by one administrator “we need to look into what an emergency-opening of the ETU looks like” ostensibly because of organizational pressure. As someone putting on the suit with a millimeter of plastic between you and headline news, it doesn’t instill confidence in the preparation.

Now before I go any further, I want to be really clear. It’s not my intention to put anyone – people or organizations – on blast. As you may guess, the government branch dealing with Ebola (USAID) and the NGO I went with (Heart to Heart) had some significant issues we were working through and around, but I don’t care to, nor enjoy, airing dirty laundry or pointing fingers. However, one of the primary reasons I quit writing, I’ve since realized, was that there were a lot of negative things occurring, but I felt guilty about writing anything other than positives. Well, I’m not gonna do that either because if I can’t write honestly, then I may as well not. Despite that, I do hope everything is said in good taste and for a purpose.

Perhaps the biggest contributor to my self-imposed censure was the rampant waste of resources and money I observed. Now, for a guy who feels a face-slap of guilt when glass goes in the trash or a half-eaten burger is bussed from a table, waste is a big deal. But this is a different level entirely. One time, in early in January I think, Dr. Taty and I were walking around Monrovia and he was explaining to me how it was his dream to someday bring his wife to stay with him in “de nicest hotel in the WHOLE Liberia, my man!”, the subtly named Royal Grand Hotel. Now to clarify, this is not Liberia-nice. This is anywhere-nice. They know they’re the nicest hotel in-country and they charge you like it – the cheapest room was I think $250-$270 per night. Expensive for the United States, but in a city where eighty Liberian dollars equal one U.S. dollar, astronomical. Apparently, President Clinton stayed here when he visited the country and breakfast is advertised as $19 like it’s a bargain. We decided to feign importance and strut to the front desk to tour a room. So we ambled across the gleaming marble with particularly straight backs and asked to see a room. “Well’, came the response, ‘we only have one room empty right now, but you can see that one.” Hm. Fifty-eight rooms of sky-high prices and they’re full? Off the elevator and onto the smoking deck we quickly saw why: occupying every table except maybe two, was the largest gathering of white people I’d seen since leaving the States. I recognized proper English and French being spoken, immediately followed by the large lanyards around most of their necks: CDC (Center for Disease Control), WHO (World Health Organization) and others. These were the foreign organizations camping out in Liberia to coordinate the management of Ebola, where they’d been stationed for a solid four to five months. Now, I’m not saying it’s evil to stay in a nice hotel, or even that these groups weren’t helping. They probably did a lot. But in a city with around 40% unemployment and where an average day-laborer earns five bucks for eight hours of manual labor, observing a booked-out hotel costing some government $15,000 a night made me sick to my stomach. Millions of dollars was being spent, but none of those dollars were getting directly to the people. Lots of that going on, from what I saw.

i had some balloons (see: the christmas tree) and it somehow came up that the kids had never had a water balloon fight. well then.

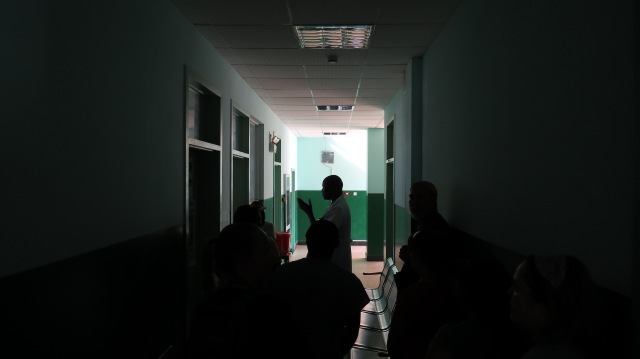

Adding to that was the management of our own ETU’s resources. Our specific locale was built to accommodate a massive influx of patients – a kind of worst-case scenario Doomsday-preparedness that seemed to be the hallmark of a lot of the Ebola plan. We were armed to the teeth with two whole warehouses worth of supplies, a full staffing matrix and enough saline in our medication stores to float a warship. Awaiting the apocalypse. When it became apparent that the torrential onslaught would in-fact be a meek trickle, a number of us were both disappointed and hopeful. It wasn’t what we planned on doing, sure, but in a destitute and impoverished area like Liberia, there were surely other ways to contribute, right? Community work, clinics, education, staffing. Being next the hospital aided that illusion, as we imagined ourselves donating boxes of medications and supplies to a large facility (second largest in-country) whose yearly operating budget was the equivalent of two months of our ETU’s. Nope, nope, nope. Red lights all around. “We’re not allowed to do anything outside the contract” was the stance. January was when we as a clinical staff officially inquired, “what else can we be doing besides Ebola work?” But when I left in mid-March, we had just begun to start teaching small, informal classes. That was it, even with less than fifteen patients total to that point.

So whose fault is that? The government? The NGO? Ours? I have opinions, but I’m not here to share those. To be sure, some of it was pure misfortune. It’s no one’s fault that the disease plummeted so quickly in Liberia, and it’s crazy to even talk about it as if more people living is a bad thing. But despite that, our operation was the Titanic: too big, too cumbersome with too much momentum to take necessary evasive maneuvers, regardless of who was manning the steering wheel. But enough negatives, you get it. And it wasn’t all bad.

So why didn’t I just write that at the time? Well, if I’m going to be really honest, I’ll say that I went into a little bit of a personal tailspin at that point. I had high hopes, and a lot of negative emotions and ideas developed that I’m, as of this writing, still processing through. I just felt useless, like I’d deceived everyone as well as myself. I didn’t write about it for a few reasons, which I can see now. First and foremost I think, pride. Everyone sent me off with such flowery language and heroic declarations, I guess I began to really want to live up to that ideal. Well, I didn’t. Now you know, ha. Feels good to say! Second, and I still worry about this a little bit, I don’t want to put people off of humanitarian work. It’s my great fear that people will hear about Ebola and the debacle that engaging it kinda was (and is) and decide that it’s not for them. I actually felt like that for a while during the trip and a little after. But someone I respect recently told me that I wasn’t giving people enough credit, and I see that now. As hilarious and fantastic of an author as I am, to think I could singlehandedly put someone off compassionate work is pretty arrogant. I’m still gonna go out and do things like this, and so should you. Lastly, my mom’s words rang in my head constantly, “It says this somewhere in the Bible, but if you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all!” Well, sorry mom. And also, that’s from Bambi, not the Bible.

To put a ribbon on it, you may be surprised to hear this – I’m kinda surprised to say it – but I’m glad I went. I remember I was really depressed one day and told a fellow nurse I felt like I was wasting my time. She, a veteran of more than a few humanitarian trips, said – which I’ll never forget – “It’s not fun, but you grow as much from negatives as from positives. You’re learning, you just don’t realize it yet.” I can say now, she’s right. The people were so kind and constantly refreshed my belief in the goodness of humanity, even as I was losing it for earlier stated reasons. Africa itself is a really weird and wonderful place. The pineapples are worth the plane ticket in themselves.

So here’s to learning, however the heck it happens.

And I suppose that’s all I have to say about that. Thanks for following along.