Day Twenty-seven.

T-minus five days until opening.

As I wrote about in my last post, building an ETU is a long, multi-faceted job. Our specific location in Tappita has been bogged down in red tape and a little too much oversight, but hope springs eternal: we officially received the keys on Friday! This means that although we’re not finished yet, we can finally start doing the modifications we need without layers and layers of approval process hovering overhead. Some of the big things still to be done include supply stock and organization, erecting another storage tent and drilling a well. The well has proved to be super-problematic; shockingly there are not many people hanging around Western Africa with a drill bit the size of my body. Also unfortunate for our plans, I had the foresight to include a no manual labor clause in my contract (called the “Perspiration Brings Resignation” addendum), so the well remains a fantasy. I simply did not bring enough Old Spice. Despite all these hurdles, our goal opening date is January fifth. It’s frustrating to delay this much – I think we all were hoping to open sooner – but the primary goal is to make sure this thing is safe and functional. You don’t get a do-over once Ebola is in the house.

While waiting on the opening, I’ve been spending most of my mornings with the Liberian clinical staff. Heart to Heart made it a priority to boost the local economy by hiring people from the surrounding villages and communities – which I really appreciate. However, we’re not at all familiar with the training and experience level of the locals, so our team was asked to develop some sort of training and orientation to the ETU. Our charge nurses – John and Kim – have a paltry fifty years of flight, critical care, emergency, managerial, education and first-responder experience combined. Obviously I –as I am sure the reader is as well – was very concerned that I was not leading the operation. But despite the glaring lack of oversight from an opinionated nurse with a decorated thirty month career, they’ve developed a really solid curriculum for the class. We’ve gone over pharmacology with a pharmacist on-loan from the States, proper decontamination from IMC (International Medical Corps: an NGO that has been working with Ebola since day one) and even a lesson on intravenous therapy from yours truly. They’re really smart and already knew everything I told them though, so I had to make up a lot of fake medical terms and say “that’s not how we do it in the States!” to save face.

Maybe my favorite thing thus far happened yesterday: a walkthrough of the hospital and a meeting with the CMO (Chief Medical Officer), Dr. Ben Kolee (Kew-lee). He is one of the real heroes of this country. A tall and lanky Liberian, he has a trustworthy face and uses large sweeping hand gestures to emphasize almost everything he says. He thanked us for coming (“You are all MOST WELCOME always in Liberia!”) and elaborated slightly on his role at the hospital in a very methodical and matter-of-fact manner. It was after we began asking questions however, that his real story began to emerge. When asked if he does any care at the hospital in addition to administrative duties, he offers a short laugh and responds, “Well, we are in Africa!”, educating us that while Liberia is a country of four million, there are only around eighty physicians currently practicing. Because of this, Dr. Kolee (an Internal medicine physician by trade) does primary care, sees patients in clinic, performs general surgery, works in the Emergency room and moonlights as an OB/GYN. All quite impressive; but it was something else he said that will stay with me.

Dr Kolee was discussing the flight of medical staff from Liberia in the early days of Ebola (such as the Chinese hospital workers) and why he did not follow:

“At the time I began hearing about Ebola in Liberia, I was also very scared with everyone else. No one knew how bad this could be. But I had heard already that many NGOs and physicians were planning to travel here to help. I thought: ‘If my house was on fire, it does not look too good for the owner to be running away as the firemen and helpers rush in to save it.’ This is my home, so I decided I must stay.” Who of us would make that sacrifice? Probably very few. Even if I never see a single Ebola case out here, meeting people like this would be worth it. There are noble people everywhere – many like this man who toil away in anonymity, a million miles from any news camera or copy of Time’s Person of the Year issue, for no other reason than an inner dedication to others.

In the movie Blood Diamond, Leonardo DiCaprio’s character – a South African diamond smuggler with perfectly tousled hair and an impressive body count – frequently says when something bad happens: “T.I.A., mahn. This Is Africa, eh?.” And while I’m sure the screenwriter has never been to Africa (I’d guess closer to Canada), it has rung somewhat true here thus far – like a tropical substitute for Murphy ’s Law. I’ll demonstrate this with an example from our ETU walkthrough this morning.

After multiple days in the classroom, it was time to take all the staff on a field trip of the ETU. The layout of Ebola treatment units vary somewhat; enough that it is helpful to see the structures in place, walk through the flow and today, to receive on-site training from our colleagues from IMC. Around seventy participants flooded into one of the white tents I’ve come to love so much, to listen to an initial lecture on how to dress in proper personal protective equipment. This about the third time we’d gotten the talk, but I attempted to look interested and keep quiet while all the demonstrations were done. The problem was, I’d accidently stood at the front of the crowd and so couldn’t browse my phone discreetly. You’d think after attending church for twenty-five plus years of my life, I’d have learned how to text in secret, but I guess the heat got to me. I wasn’t the only one. As I scanned the room to keep my mind busy, my eyes fell on a hygienist that seemed to be bobbing his head to some kind of music – the problem being of course that there wasn’t any music. In the second that followed, I noticed he was wearing a winter coat, pouring sweat and had flickering eyes.

He was definitely going down.

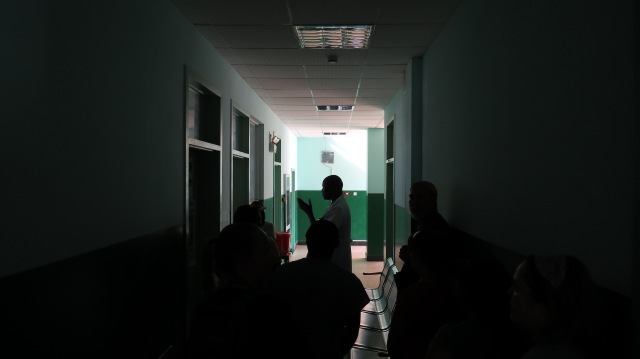

some of their wards are actually not bad. Dr Kolee explained that this was because they were constructed by the Chinese after Taiwan built a hospital over the hill (now defunct). Notorious rivals, the Chinese decided to add a little extra flair, I guess?

Without thinking, I bounded a few steps across the room and grabbed the material at the front of his jacket, calling for a chair just as his legs went rubbery. It took everyone a quick second to realize I wasn’t attacking a friendly Liberian, before we got the poor guy a chair and sat him down. I was checking a radial pulse and trying to bring him around, when a voice behind me said, “Zach, step back! You don’t have any gloves or anything on.” I was about to flip around and say “Really? Gloves, right now?” in the condescending way only an ED nurse perfects, when I realized something everyone else already had. This is an ETU. In Liberia. In the midst of a horrifying viral outbreak.

Um, right. Gloves.

In retrospect, it’s fascinating to watch a room full of trained health care professionals respond to something like that. In the less than twenty seconds it took for me to step away and begin donning my own PPE, a few nurses had already put on most of theirs, and the physicians had started organizing a plan. I felt a small wave of fear wash over me – had I exposed myself to an Ebola patient? – but pushed it out of my mind almost immediately: Think of the criteria! Fainting by itself isn’t criterion for diagnosis! (Note: The five criteria for Ebola suspicion are: 1. Contact and fever, 2. Contact and three symptoms, 3. Fever and three symptoms, 4. Unexplained bleeding and 5. Unexplained death. For a more detailed explanation, click here.) As I was raising my own spirits and pulling on my last glove next to two other nurses and Dr. Ravi, I overheard his friend say: “Don’t worry about him, he has just been thinking a lot about his father. He is really sick at home.”

Oh boy. Happy thoughts.

it’s weird to see a hospital that is relatively empty. this is when the power goes off for four hours a day, to rest the generators

We quickly parted the large, gawking crowd and the four of us in protective equipment shuttled the poor, embarrassed hygienist into the unfinished ETU. During the interview, he expressed he was feeling better and had no symptoms, but was just worried about his father. At the same time, we were relayed a message from a different community member, who said the patient’s father had actually died earlier that day, but that there may be some family denial. Which was sad to me for two reasons: one, it’s his dad. Two, it meets criteria.

So as not to keep you in painful suspense, we ended up not keeping the patient. When we began to ask about his father’s symptoms, he talked to us about slurred speech, one-sided weakness, inability to swallow or eat, and gait problems – which sound exactly like stroke. He also looked markedly better after a banana and water, had no fever and denied other problems. After a lengthy, spirited discussion (with fifty onlookers), the physicians agreed that this patient did not meet case criteria and therefore did not need to be transferred to another ETU. Ya know, because we have no water or beds yet.

My faith in our physicians remains unshaken, but I was allowed to leave class a little early to take what may be the longest shower African has ever seen.

TIA, indeed.